Japanese Release Boom Boom Live 1976

New Rose Release of Willie Alexander and the Confessions French Live Tour 1982

Taxi-Stand Diane, New Rose Records, 1983

Private WA

Persistence of Memory Orchestra. 1993 Willie, Ken Field and Mark Chenevert on sax, Jim Doherty on drums.

East Main Street Suite, The Persistence of Memory Orchestra, 1999

Boom Boom Band, Dog Bar Yacht Club, 2005

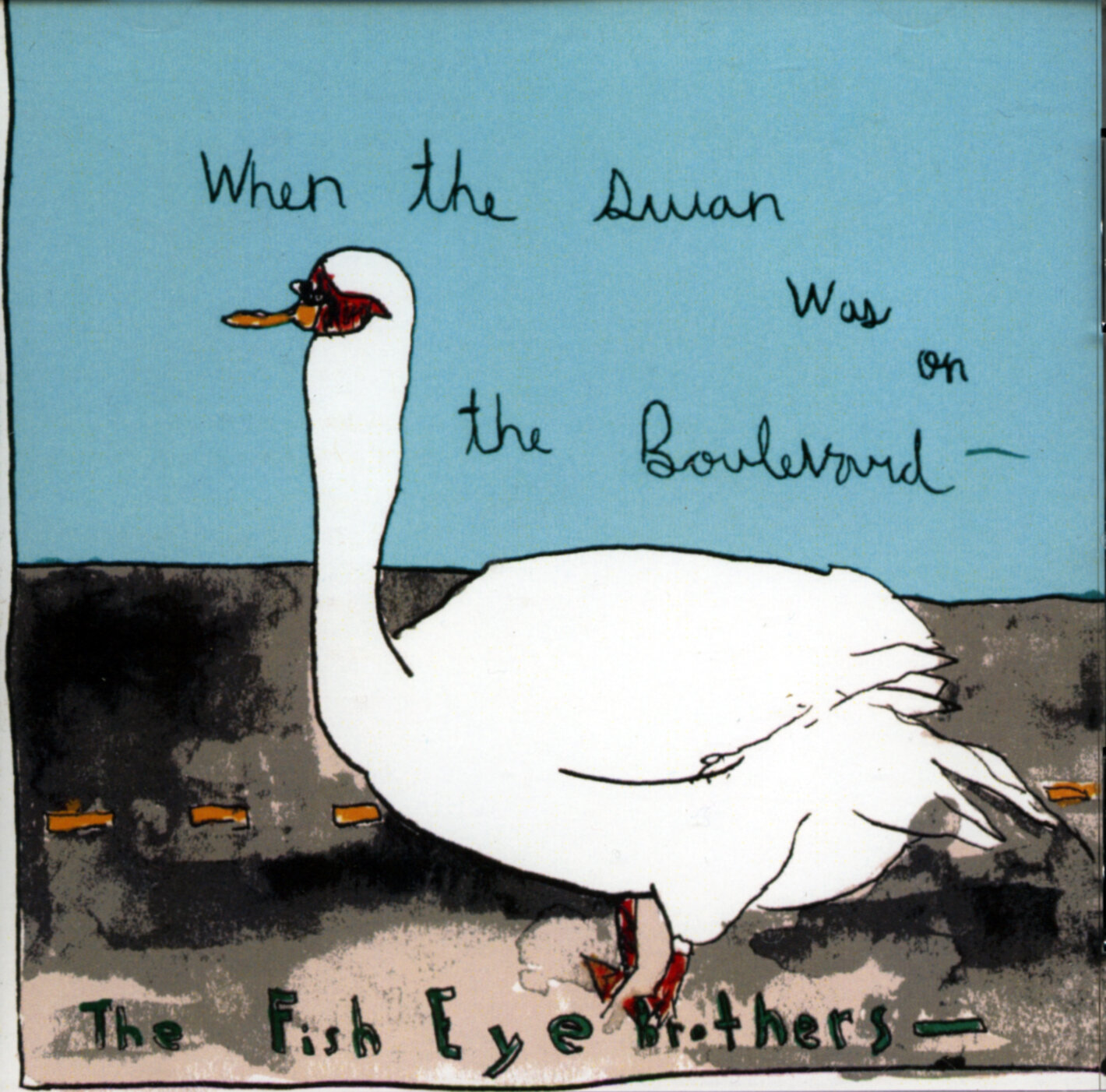

When the Swan Was On the Boulevard, Fisheye Bros, Willie (keyboard) and Jim Doherty (drums), Mark Chenevert (sax)

The World Famous Non-Stop Seagull Opera Meets the Fishtones at the Strand.

Song samples and downloads available in the store.

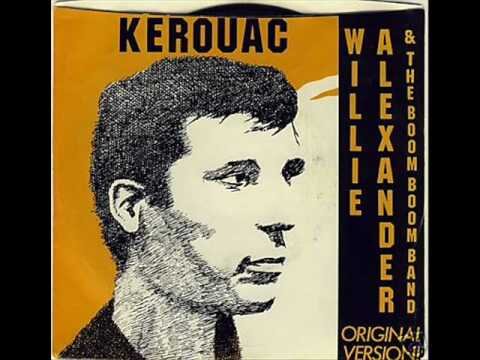

Willie Alexander and the Boom Boom Band

Trouser Press Review

Boston scene patriarch and would-be Beat Generation holdout Alexander is an intriguing and unique historical figure, the eternal ghost of the Rat who has raved and played through more musical eras than most musicians have even survived. The irrepressible singer/pianist’s redoubtable résumé goes back to the ’60s and includes such groups as the Lost, Bagatelle, Bluesberry Jam, Grass Menagerie — even a stint in the post-Lou Reed Velvet Underground. If he was never really a punk (despite such conceptually righteous songs as 1976’s “Hit Her wid de Axe”), Alexander’s intelligence and commitment to rock’n’roll purity (minus the eternal adolescence) made him a part of the punks’ underworld; maturity and boundless enthusiasm for writing and performing music has always sustained him.

Willie Alexander and the Boom Boom Band is dedicated to Jack Kerouac, and includes Alexander’s tributary song about the author, which was a cult hit when it first appeared on a 1975 independent single. The song’s a heartfelt standout; the rest of the record is routine bar-band rubbish, wanting for both songs and style. Meanwhilefollows the same path, but is notably better, thanks to Alexander’s looser singing. For him, sloppiness is definitely an asset.

Willie left the Boom Boom Band behind for Solo Loco (the appellation is a tribute to Latin pianist Joe Loco), relying instead on his own keyboards and percussion, with some outside guitar assistance. The record is a real departure, using occasional synthesizers to support extended, moody numbers that refer back to his earliest recorded work, and a voice that seems at once weary and sanguine. The material is uneven; when it’s good, the record shines brightly. (Solo Loco was originally released in France by New Rose; the American version is slightly different.)

Autre Chose — two disques of live Willie — was recorded in France during a March/April 1982 tour with a new backing trio. The choice of material is eclectic, beginning with “Tennesse [sic] Waltz” performed a cappella and including all of his best(-known) songs, plus some new things.

The Confessions on A Girl Like You (recorded in an American studio but unreleased outside France) include a saxophonist, the same bassist and guitarist from the live LP, but no drummer; Willie (a qualified percussion practitioner) picks up the sticks for this effort. Like a low-key version of a ’70s Rolling Stones album, there’s a little rock’n’roll, a blues number, lots of sex, a few choice covers and some good times. A career high-water mark, A Girl Like You (dedicated to Thelonious Monk) shows various sides of this mature — if limited — performer.

Continuing along his odd Boston-and-Paris path, Alexander recorded a spare album that excludes guitar and rock in favor of keyboards for a bluesy, late-night sound: Tap Dancing on My Piano has the loose, funky feel of old friends tinkering in the studio. Basically, Willie accompanies himself on piano with varying amounts of harmonica, sax and drums thrown in for accent. There’s nothing here you would call arranged: even the busiest tracks sound like a first rehearsal. The boozy, seemingly extemporaneous “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” is a heartwarming highlight; the rest varies from Randy Newmanesque (“The Ballad of Boby Bear,” named after a drummer of Willie’s acquaintance who does spell it that way) to the bizarre (“Me & Stravinsky Now”). A modest and appealing slice of sincerity.

The Dragons Are Still Out finds Alexander back to rocking with a full-strength rock trio, horns, co-producer/co-writer Erik Lindgren on keyboards and even a cellist. Fearlessly covering a wide range of styles — from a unique interpretation of “Slippin’ and Slidin'” to the improvised weird-piano autobiography of “Me and Dick V.” and the inadvisable (but not completely embarrassing) “WA Rap” — as well as more typical (and more exotic) fare, The Dragons Are Still Out proves that this old-timer is neither out of touch nor out of tricks.

In light of Alexander’s discographical complexity, Willie Loco Boom Boom Ga Ga 1975-1991 is better than one-stop shopping, it’s the only opportunity for a newcomer to glean a sensible career summary without spending years searching out now-rare import vinyl. The sloppy, spirited festival of bands, unpretentious sounds and songs (22 in all) is neatly annotated by the star. (Sample: “I wrote this [‘Kerouac’] in my bathtub in two minutes after thinking about Jack for 20 years.”) There’s nothing fancy here, but Alexander’s plainspoken writing and skilled from-the-heart delivery of original songs that chronicle people (“Taxi-Stand Diane,” “Abel and Elvis,” “Dirty Eddie”) and places (“Mass. Ave.,” “At the Rat”) make this an invaluable diary of a rocker. (Not, it needs to be noted, a rapper.)

But Alexander is also one hell of a spoken-word artist, a talent he’s also explored on record. Private WA, a collection of studio recitations and diary entries with ambient keyboard accompaniment recorded between 1984 and 1990, makes the personal compelling and sharp-focuses the universal. A bit heavy on the Burroughsian delivery at times (once a would-be Beat, always a would-be Beat), but consistently revealing and engaging.

The most contemporary track on 1975-1991 is the previously unreleased debut of the Persistence of Memory Orchestra. A full album by that quartet-Willie singing and playing piano with two horn players and a drummer-became his first new American all-music release in a dozen years. “I’m like Rip Van Winkle waking up from his nap,” sings Alexander in the autobiographical “Fishtown Horrible,” and it’s true: this hairyassed but somehow cogent rock/fusion jazz/rock (all loosely laced, with hip-hop and Suicide-al techno accessories) has the recharged imagination of a young turk rubbing his eyes in anticipation, not an aging dozer settling in for the late innings. With wholly reimagined versions of such oldies as “Mystery Train” and Alexander’s own “Shopping Cart Louie,” the record is smartly produced, bizarre and thoroughly unpredictable — an improbably welcome creative rebirth . Ira Robbins